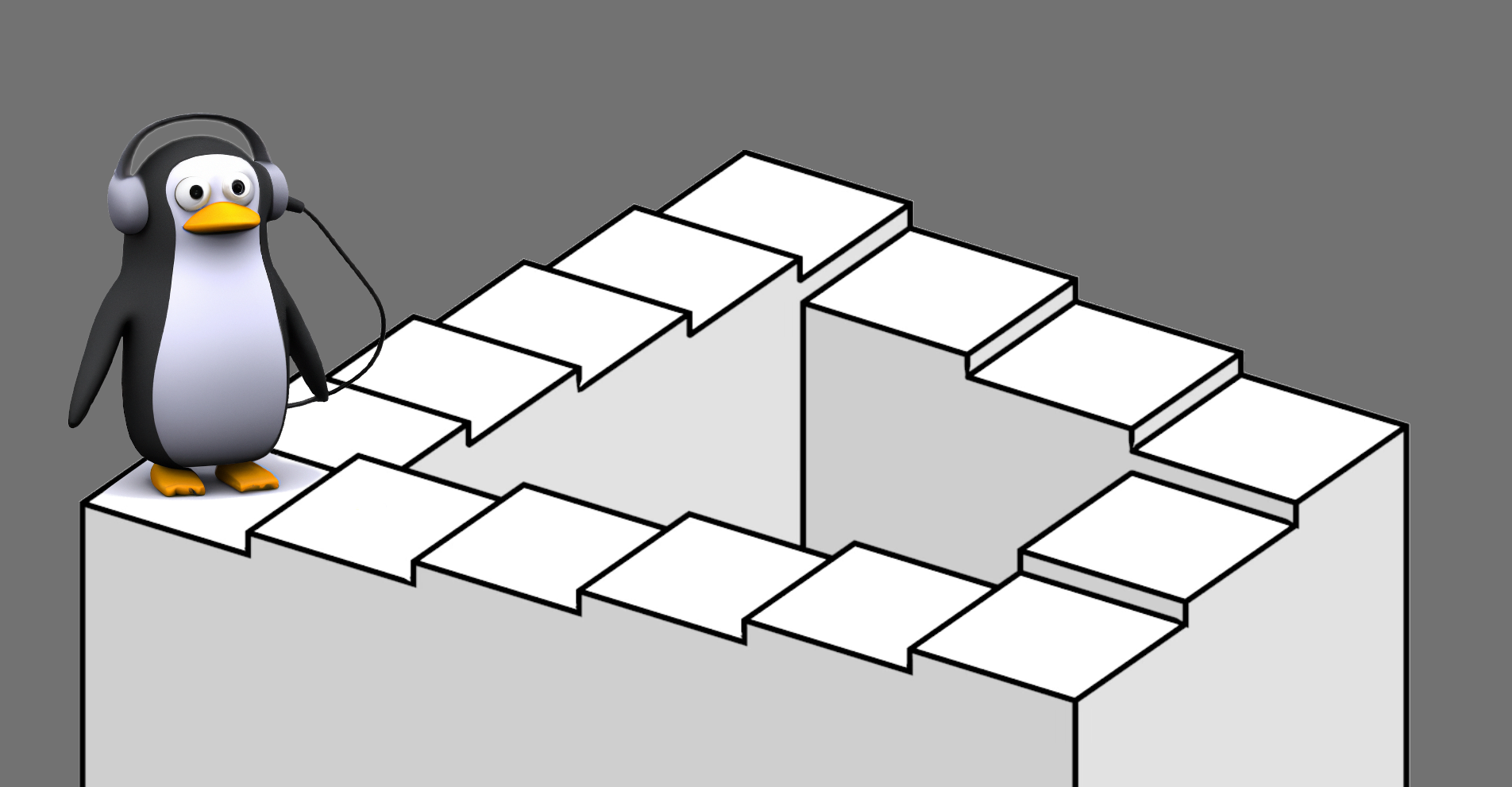

Penrose Stairs

Background

Penrose’s steps, made famous in many drawings by Maurits Escher, provide a rather close analogy for much of what we see in the current in-ear monitor market. As with many nascent technologies, IEMs made big improvements in their formative years, but have now matured and reached something of a plateau where meaningful improvements appear to be increasingly difficult to achieve. How does an industry that wants to increase sales volume year after year respond to this? How do they get you to purchase yet another pair of headphones – one which isn’t any better than any of those you already own?

Long before Apple’s famed ‘planned obsolescence’, lightbulb manufacturers solved the problem of diminishing sales by designing bulbs with intentionally limited lifespans. Ifixit.com recently named their worst-in-show ‘enshitification’ (yes, according to the American Dialect Society, that’s really a word) award to Sennheiser’s Momentum True Wireless 4 earbuds on account of their planned obsolescence, i.e., Bluetooth headphones with batteries that the user cannot replace and that the OEMs will refuse to replace.

Ironically, true-wireless Bluetooth headphones is one area where HypetheSonics is still seeing some audio-quality improvements being made. This is partly from Bluetooth earbuds having started from such a weak position, but also from them having the advantage of being able to create a genuinely-plausible, realistic soundstage via DSP – something which conventional wired two-channel audio can never achieve, regardless of phase response, because of the missing crossfeed. The stall, or plateau, we are talking about here in audio quality is mainly related to wired two-channel IEMs. Luckily for audio manufacturers, they don’t need existing products to break to push new sales. Unsound marketing and misinformation in this area can easily exploit our fear of missing out, our relentless psychological need for an ‘upgrade’, and the apparent belief of many audiophiles on many mainstream audio-marketing sites that there is no limit to how much better a headphone’s performance can get. The further belief among many audiophiles that you can always trust your ears allows IEM manufacturers to leverage influencer-driven hype, placebo and expectation bias, even if objective improvement is non-existent. Manufacturers don’t need to lie in their product marketing – they can simply have their various online shills and reviewers do this for them.

The Penrose Step Analogy

Consider a hypothetical selection of headphones, A through G. You’re performing a careful listening test to determine which headphone is the ‘best’, or at least, which constitutes an improvement worthy of your hard-earned pennies. For the sake of this experiment, let’s assume that each headphone’s performance can be ranked by the pitch you hear. Compare A vs B, and rank the ‘winner’ as the headphone with the higher pitch. After all, being able to reproduce higher frequencies is indeed associated with better resolution. Now compare the winner of this first test with headphone C. Now compare the ‘best’ of these first three headphones with headphone D, and so on. By the time you reach headphone G, you should have found the ‘best’ of all these headphones. Now compare that headphone directly against headphone A. Now which headphone is the ‘best’?

- A

- B

- C

- D

- E

- F

- G

This illusion can be better understood by putting an octothorpe character after the C, F and G. (Musicians will note it’s actually an A major scale transposed into the key of C.) What’s happening here is strikingly similar to what happens with many product ‘upgrades’: some aspects get better and some new features are added, but at the same time other aspects get worse and certain useful features get removed.

Providing a new product which appears to be an improvement, year on year, is a rather easy game for headphone manufacturers. There are an infinite number of permutations to a headphone’s tuning and so an infinite number of nuances to this trick, but the following describes one of the more obvious tactics. Take a headphone that might sound a bit dull and lifeless, and tune in a bit more bass and treble, producing a headphone that sounds more fun and engaging. Next year, flatten out the frequency-response curve to produce a more reference, audiophile-like sound. Rinse and repeat. Manufacturers and their online army of reviewers and sales affiliates can seal the deal by claiming that each new headphone has a night-and-day improvement in ‘technical performance’ – a term that is, conveniently, so ill-defined that it can’t really be refuted with any objective data. Are the reviewer’s ears and brain so astute that they’re able to perfectly isolate and separate the effect of mean amplitude versus frequency? What about mean phase? Is isolating these effects even the goal? Nobody, including that reviewer, knows the answer to this. Placebo and expectation bias likely mean that many reviewers will genuinely believe they are hearing an improvement, even when they’re not.

Of course, newer technology teases the promise of further improvements. This was true with planar magnetic drivers, electrostatic drivers, and now with the newer MEMs drivers, but the fact is that the harmonic distortion profiles of all these drivers tend to closely mimic those of their predecessors. For example, planar magnetic drivers tend to exhibit even-order harmonic distortion at similar levels to that of dynamic drivers. Electrostats and MEMs drivers tend to exhibit odd-order harmonic distortion at levels similar to those of balanced-armature drivers. Which of these tends to give the lower levels of harmonic distortion? The winner here is, somewhat ironically, the oldest of all these technologies – the dynamic driver, which is celebrating its one hundredth birthday this year.

As interesting as it might be to see what benefits MEMs drivers could have in future active-noise cancelling (ANC) headphones, we’re doubtful that any of the current claims about this technology are actually going to be a direct benefit to the consumer. Claims about MEMs drivers being ‘faster’, or having lower distortion have not been borne out in any of our tests (for example, see our assessment of the Aurvana Ace 2). While there could be some cost benefit to mass producing drivers with better tolerance, that’s more likely to lead to higher profit margins for OEMs than to lower prices for consumers; newer audio hardware is never less expensive. One interesting claim about future ANC benefits is touted in the upcoming low-frequency ‘Cypress’ xMEMs driver, which is said to be able to achieve 140 dB at 20 Hz via ultrasonic modulation. 140 dB in your ear sounds outrageous, but makes some sense if you want earbuds that can cancel very loud external sounds. However, without perfect demodulation (and we are skeptical about achieving this with silicon valves), the process of such ultrasonic modulation leaves a residual high-frequency 140 dB carrier wave. If a Cypress driver is also used to deliver low frequencies (replacing the dynamic driver in the Aurvana Ace 2), bass frequencies are also going to constantly bombard users’ ears with modulated ultrasound. High amplitude carrier waves will be required for good low-frequency response on account of the equal-loudness curves, and high-amplitude ultrasound is capable of damaging hearing even though it’s inaudible. Based on what we’ve seen and heard so far, we would not want to put an xMEMS Cypress driver in our ears.

Even if some new technology, or slight permutation of drivers within the existing technology framework, does correlate to some statistical improvement under blind test conditions, the unique nature of every individual’s HRTF and the dependence on any other headphones that a listener had acclimated to prior to any comparison makes the entire process subjective to the point of irrelevance. Ultimately, this can lead us all round an infinite staircase that need have no overall upward trend.

The ubiquity of free automatic equalizer tools on websites such as HypetheSonics means that any cheap dynamic-driver headphone can now be made to closely match the frequency response of any other headphone, and in fact can likely to do so with lower harmonic distortion. But wait… someone is going to tell you the ‘technical performance’ is better on the newer, more expensive product. As with all good lies, there could be a tiny element of truth to this, because even with a perfect equalization, headphones will give rise to different waveform errors. However, that is almost certainly not what these reviewers mean by ‘technical performance’, and you can count on no fingers the number of reviewers anywhere that are backing up such statements with objective measurement data.

Summary

We consider ‘technical performance’ to be the last bastion of unsound, pernicious marketing. Unfortunately, because of direct or indirect sales, online advertising revenues, paywalls, subscriptions, donations, or just a continuing supply of free review samples, almost all online reviewers and third-party audio marketing sites that masquerade as audio ‘community discussion’ websites have a strong financial incentive to perpetuate this nonsense. The finances behind all this mean we are inextricably stuck on the staircase.

—————————————————

Did You Know?

All products on our databases come with a ‘microHype’ – brief subjective thoughts and impressions on the product and its ranking. To access the DAP microHypes, simply click on the slide for that DAP. To access the microHype for a headphone, click on the name of the heaphone once displayed, or click on the (red) score in any rank/search result. Certain products that are regarded as special, or particularly relevant or interesting, have more extensive reviews in the form of ‘miniHypes’. The latest miniHype is always displayed on HypetheSonic’s front page, with archived miniHypes shown below.